The Marines typically select their commandants from the ranks of the infantry. Jim Amos, however, was the first (and to this date, the only) naval aviator selected to lead the Corps. His call sign “Tamer,” General Amos flew the muscular F-4 Phantom and later the F/A-18 Hornet.

He was one of only two commandants to have their careers punctuated by short stints in the civilian world: the 11th Commandant, Major General William Biddle, retired in 1914 but returned to service during World War I. General Amos got out in 1978 and flew commercially for Braniff Airways for a couple years before rejoining the Marines in 1981 (around the time I was a young lance corporal).

Another distinguishing feature of his service as Commandant had less to do with Jim Amos and more to do with his wife, Bonnie. She was known as a tenacious advocate for military spouses and children, working tirelessly to influence Marine Corps and DOD policies and programs that improved the well-being of military families. She was a legend herself: her pride in the Marine Corps came through in the enthusiastic tours she gave of the Commandant’s House at 8th & I in Washington, DC. She was known as "The First Lady of the Marine Corps," and her detailed tours of the residence even earned an informal brand: “The Bonnie Amos Tour.”

And General Jim Amos was a reader, as are most great leaders. We’ll come back to this.

The summer of 2019, some of our family had a chance to tour the Commandant’s House, courtesy of my brother John, a Marine lieutenant general who is getting ready to retire this year after 35 years of service. It was a brief walk-through, a half hour before the garden reception that preceded the weekly Evening Parade. It wasn’t a full-fledged Bonnie Amos-type tour, but a 30-minute historical overview, presented in the sitting room and music room by a young Marine docent by the name of Corporal Nathaniel Hunt-Kelly.

He checked off some likely historical explanations, one of which was that the Brits so respected the valor of the 200 Marines who defended the Barracks and the residence, they opted not to burn those buildings. I spoke up and said, “It’s a little reminiscent of Thermopylae, isn’t it?” (referring to a battle from Greek history where a small band of warriors held their ground against a numerically superior foe).

The young corporal cocked his head and said, “Since you mentioned it, follow me.” He walked us next door into the music room. Against the south-facing windows sat a piano with John Philip Sousa’s pen and inkwell on top, and a leaded-glass Tiffany lamp beside. On the walls hung portraits of past USMC commandants. As we circled around, Cpl. Hunt-Kelly gestured to the painting of General Amos and began talking.

The young corporal cocked his head and said, “Since you mentioned it, follow me.” He walked us next door into the music room. Against the south-facing windows sat a piano with John Philip Sousa’s pen and inkwell on top, and a leaded-glass Tiffany lamp beside. On the walls hung portraits of past USMC commandants. As we circled around, Cpl. Hunt-Kelly gestured to the painting of General Amos and began talking.

Much of Jim Amos’s career had been atypical. No other commandant had come from the air wing. No other commandant had exited the Marine Corps to fly for an airline, only to rejoin and then rise to lead (what the biased among us would call) America’s finest fighting force. His official portrait would turn out to be atypical, as well.

The corporal pointed out some features in Tamer’s portrait that appeared in no other commandant’s. In the painting, General Amos stands in front of a bookshelf that displays only a few items. At his right hand (significantly) is an image of Bonnie. Corporal Hunt-Kelly said, “When the general said he wanted his wife included in his official portrait, he was told, ‘Sir, we don’t do that.’ The general responded, ‘We’re doing it on this one.’”

On the next shelf appeared the model image of the F/A-18 he flew, reflecting the distinction of being the only Marine aviator to have served as commandant. Above that, a folded flag in respect for all the Marines and others who’d given what Abraham Lincoln had called “the last full measure of devotion.”

The corporal then looped back to where we started. He told, in brief, the story of the battle in 480 BC between the Spartans and allied Greeks against the invading Persian army, fought at the narrow seaside passage known as “Thermopylae” (translated as “the hot gates,” for the sulphur springs that bubbled up from the ground there).

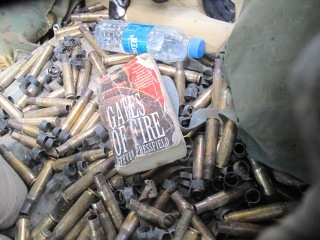

Cpl. Hunt-Kelly gestured to the books painted into the top shelf in the portrait. He said, “An author and Marine veteran by the name of Steven Pressfield wrote a novel, Gates of Fire, based on the battle at Thermopylae. General Amos held the book in such high regard that he had it painted into his official portrait.”

I looked across the room to Jill and our eyes met with raised brows. Steve had been a friend for several years by that point. I had mentioned to him that we were going to DC and would be getting a tour of the Commandant’s House. Steve had responded with his own story about being an overnight guest of Bonnie and General Amos at the residence, and how he enjoyed the accommodations in “The Chesty Puller Suite.”

At my first chance, I fired off an email to Steve: “Hey, man... I’m sure you know about this, but we just got out of this tour and yada-yada-yada your book, blah-blah-blah in General Amos’s portrait.”

Steve was surprised. And I was surprised that he was surprised. “I did NOT know about Gates of Fire being in his portrait,” he said. “But it makes an old lance corporal proud.”

1 comment:

Great piece!

Post a Comment