"Patient or visitor?” the valet asked each driver arriving at the treatment center. Sander had been shaving his head since the Navy. His smooth pate had nothing to do with chemo, but the parking guys didn’t know that. In this case, Sander didn’t mind being profiled. If they didn't bother to ask him "patient or visitor," he was fine with that. He felt like he was undercover, with cheap parking.

"Patient or visitor?” the valet asked each driver arriving at the treatment center. Sander had been shaving his head since the Navy. His smooth pate had nothing to do with chemo, but the parking guys didn’t know that. In this case, Sander didn’t mind being profiled. If they didn't bother to ask him "patient or visitor," he was fine with that. He felt like he was undercover, with cheap parking.He registered, let the clerk tag him with a barcoded wristband, and settled into a seat with a dog-eared copy of Sports Illustrated. Lindsey showed up, kissed him on the forehead, and planted next to him.

Any trouble getting away from work, he asked. She shook her head no. “They know about us,” she said. “When have I ever missed one of these?”

The waiting room was modern. No right angles and curved windows running floor to ceiling and facing south to catch the sun, clusters of tall bamboo alternating with stands of ficus to give the room some green and some life. People sat alone or in groups of twos or threes, the chairs in muted colors and soft enough to be comfortable, but solid enough for a patient to push herself up unaided. If not for the faint smell of disinfectant, you might have forgotten you were in a hospital.

Sander and Lindsey talked through the week’s schedule: Sarah’s got clarinet on Wednesday, Maggie’s soccer practice on Thursday, whose turn it was to go to Costco. He fingered the patient bracelet while they talked, his eyes going to the colors and shapes that spiraled into the sleeve of tattoos running up his arm. Tribal whorls, ivy and barbed wire, a rose. A mermaid, a snake coiled around a dagger, a shark. An anchor, bracketed by the names of every ship he’d served on.

His eyes drifted around the room. Some people fidgeted. Some dozed. Some looked worried or nervous. All looked tired. A woman, pale and thin and bundled in fleece, held herself with her arms and looked chilled despite her layers. She moved to the windows and found some warmth in the sunlight that spilled into the room.

Across from Sander and Lindsey, an old man in coveralls, sideways in his wheelchair, a mask covering his mouth and nose, on his head a faded green cap with the image of a bounding deer.

A woman steadied herself on her husband’s arm as they made their way to the registration desk. Her head was turbaned in a bright silk scarf, a batik of color in apple, olive, and turquoise.

“Marilyn Wolf,” she said, “to see Dr. Sufi.”

The clerk tapped out the name while Marilyn Wolf glanced to the rack of brochures with titles like “Radiation Therapy: How It Helps” and “Coping with Your Diagnosis: Tools to Help You Live.”

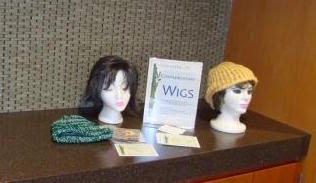

Sander watched her, and followed her gaze to a poster along the wall:

“Complimentary Wigs. See your patient representative for information.” Stylish samples sat perched on white Styrofoam heads.

Marilyn Wolf’s eyes lingered there. She reached to straighten the knot on her scarf. She straightened her shoulders and turned away from the display. Sander could hear her say to her husband, “Take me to a seat, will you, dear?”

Lindsey watched Sander watching Marilyn Wolf. She laid her hand on Sander’s.

Sander had told Lindsey he was glad he wasn’t like these people. Oxygen tubes in their noses, their surgical scars, and their chemo-fried hair. Their ill-fitting wigs and canes and wheelchairs. I’m glad that’s not me, Sander had said. Sander had run three miles and done 50 pushups this morning. He was doing just fine.

He didn’t belong here, he told Lindsey. He felt like the narrator in that Chuck Palahniuk novel. A tourist, a voyeur. Visiting his brain parasite survivors group on Thursday, his bowel cancer support group on Friday, and his sickle cell group every other Saturday. He had one little lump. Not like these poor folks, he said.

All Lindsey said was, "You’ve all got something, never mind how much of it you’ve got." He didn’t want to hear it. I'm kind of like Forrest Gump in these waiting rooms, he said. Shot in the ass and eating ice cream, surrounded by all these Lieutenant Dans. Pretty lucky, when you think about it.

“Chapin? Mr. Chapin?” A nurse called his name and walked them back to an exam room.

They emerged later, a piece of paper in Sander's hand. He had underlined the words: “Nodule previously described – no increase in size or number.”

Eyes in the room were on Sander and Lindsey, as eyes were on each person who emerged from the exam area. Each next one carried with them a verdict – a reprieve or a sentence or at the very least, a continuance. For the room, that verdict was not their own. They would learn their own soon enough. But they watched.

Sander looked at his paper and beamed at the words he’d underlined. He felt light. Triumphant. He raised his hand to give Lindsey a high-five.

Lindsey glanced to the room and gave him a quiet smile and stepped past his raised hand, pressed against his chest and whispered, “I’m happy for us. But later. Let’s be happy later.”

Sander met Lindsey's eyes with a question. She tipped her head in the direction of Marilyn Wolf and the farmer and the woman warming herself in a shaft of sunlight next to a stand of bamboo, all of them looking at Sander and Lindsey.

Sander looked, turned back to Lindsey to give her a slow and single blink – in the wordless language of two who’d been married 23 years: “I understand.”

They turned to leave and saw another temporary resident of this place, a woman in a business suit, her hair short, her build trim and professional. She sat with her ankles crossed, speaking into her phone. The exam room doors hummed open and, now spectators with the rest of them, Lindsey and Sander turned to look.

They took him to be her husband. In a red polo shirt and jeans, he walked toward her at a shuffle, his eyes to the ground. “I’ll call you later,” she said into the phone, slipped it into her handbag and stood to face him.

As he passed, Sander saw him raise his eyes to his wife, wag his head twice, slowly, and turn his eyes back to the carpet. As if being turned on a dial, the expectant look on her face slowly constricted, her eyes reddening and going wet. She raised her arms and held them out to him.

He moved into her, like a boat coming to berth. His arms came up to return her embrace and his shirt cuff rode up his bicep. Sander could see blue and green ink, the bottom edge of an anchor with the words “US Navy” in a rocker beneath.

They held each other for a long time, their heads on each other’s shoulders. Sander and Lindsey did not move, but turned to each other. By the tilt of Lindsey's head and how she narrowed her eyes and pointed her chin, Sander gathered what she was thinking. Without words. Because they’d been doing this for 23 years, after all.

The man and his wife released their embrace, wiping their eyes and reaching for composure. Sander looked at Lindsey and she nodded. Yes. Go ahead.

Sander approached and cleared his throat politely. They turned to him. Sander gestured to the man’s tattoo.

“Shipmate,” he said, pausing and figuring what to say next. “My name is Sander. We've... we've got some things in common."

****

Photo Credits:

Anchor tat, Creative Commons via Flickr, GreggMP

Scarf, Creative Commons via Flickr, Jenny Mealing

Complimentary Wigs, public domain

Lindsey watched Sander watching Marilyn Wolf. She laid her hand on Sander’s.

Sander had told Lindsey he was glad he wasn’t like these people. Oxygen tubes in their noses, their surgical scars, and their chemo-fried hair. Their ill-fitting wigs and canes and wheelchairs. I’m glad that’s not me, Sander had said. Sander had run three miles and done 50 pushups this morning. He was doing just fine.

He didn’t belong here, he told Lindsey. He felt like the narrator in that Chuck Palahniuk novel. A tourist, a voyeur. Visiting his brain parasite survivors group on Thursday, his bowel cancer support group on Friday, and his sickle cell group every other Saturday. He had one little lump. Not like these poor folks, he said.

All Lindsey said was, "You’ve all got something, never mind how much of it you’ve got." He didn’t want to hear it. I'm kind of like Forrest Gump in these waiting rooms, he said. Shot in the ass and eating ice cream, surrounded by all these Lieutenant Dans. Pretty lucky, when you think about it.

“Chapin? Mr. Chapin?” A nurse called his name and walked them back to an exam room.

They emerged later, a piece of paper in Sander's hand. He had underlined the words: “Nodule previously described – no increase in size or number.”

Eyes in the room were on Sander and Lindsey, as eyes were on each person who emerged from the exam area. Each next one carried with them a verdict – a reprieve or a sentence or at the very least, a continuance. For the room, that verdict was not their own. They would learn their own soon enough. But they watched.

Sander looked at his paper and beamed at the words he’d underlined. He felt light. Triumphant. He raised his hand to give Lindsey a high-five.

Lindsey glanced to the room and gave him a quiet smile and stepped past his raised hand, pressed against his chest and whispered, “I’m happy for us. But later. Let’s be happy later.”

Sander met Lindsey's eyes with a question. She tipped her head in the direction of Marilyn Wolf and the farmer and the woman warming herself in a shaft of sunlight next to a stand of bamboo, all of them looking at Sander and Lindsey.

Sander looked, turned back to Lindsey to give her a slow and single blink – in the wordless language of two who’d been married 23 years: “I understand.”

They turned to leave and saw another temporary resident of this place, a woman in a business suit, her hair short, her build trim and professional. She sat with her ankles crossed, speaking into her phone. The exam room doors hummed open and, now spectators with the rest of them, Lindsey and Sander turned to look.

They took him to be her husband. In a red polo shirt and jeans, he walked toward her at a shuffle, his eyes to the ground. “I’ll call you later,” she said into the phone, slipped it into her handbag and stood to face him.

As he passed, Sander saw him raise his eyes to his wife, wag his head twice, slowly, and turn his eyes back to the carpet. As if being turned on a dial, the expectant look on her face slowly constricted, her eyes reddening and going wet. She raised her arms and held them out to him.

He moved into her, like a boat coming to berth. His arms came up to return her embrace and his shirt cuff rode up his bicep. Sander could see blue and green ink, the bottom edge of an anchor with the words “US Navy” in a rocker beneath.

They held each other for a long time, their heads on each other’s shoulders. Sander and Lindsey did not move, but turned to each other. By the tilt of Lindsey's head and how she narrowed her eyes and pointed her chin, Sander gathered what she was thinking. Without words. Because they’d been doing this for 23 years, after all.

The man and his wife released their embrace, wiping their eyes and reaching for composure. Sander looked at Lindsey and she nodded. Yes. Go ahead.

Sander approached and cleared his throat politely. They turned to him. Sander gestured to the man’s tattoo.

“Shipmate,” he said, pausing and figuring what to say next. “My name is Sander. We've... we've got some things in common."

****

Photo Credits:

Anchor tat, Creative Commons via Flickr, GreggMP

Scarf, Creative Commons via Flickr, Jenny Mealing

Complimentary Wigs, public domain

No comments:

Post a Comment