I felt welcomed along on this particular journey.

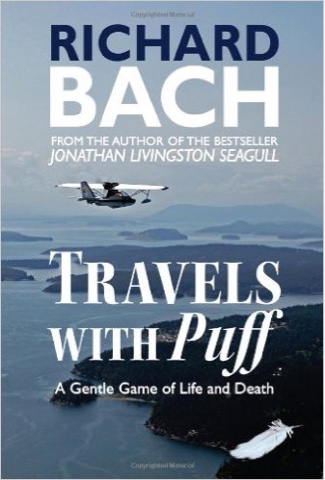

Richard brings us with him as he travels from his home in Washington State to the lakes of central Florida. Here he is introduced to his new light amphibian seaplane, a SeaRey we come to find has named herself: Puff.

We're introduced to Puff and find she's like a skittish filly, or a young lady abandoned if not orphaned. Of two previous and careless owners, the most recent "was pretty sure he didn't need a checkout" and promptly clipped a tree on a takeoff.

"He doesn't care for the airplane, now, doesn't want her anymore." Puff is not one to trust pilots.

Though already an experienced aviator, Richard spends the time to get to know her. He trains to fly her with a beginner's mind, that of a green cadet. He slowly builds his trust in her, and hers in him. He invests the time to learn her ways. How does she handle in what kinds of winds? How heavy or light does he need to be on her controls? What are the ins and outs of her handling on water takeoffs versus runway takeoffs?

It's a courtship, really, as Richard and Puff get to know one another, building friendship, coming to trust and then respect, and even love. As intimates do, they move toward becoming one, as Richard put it, "... a pilot unmoving, alone with his new airplane on that silent beach, two futures now locked together, stretching way out ahead where it's all just fog."

We meet Richard's coach for his advanced SeaRey training on those lakes of central Florida. Fellow pilot Dan Nickens is "a tall calm gentleman, the easy way about him of a favorite high-school teacher." On top of being Richard's flight instructor, Dan is also a geologist and a photographer -- and took the colorful photos that appear on the pages of this book.

Richard describes Dan: "...one hour he's flying 80 mph, inches over the uncaring wavetops, the next I imagine him installed at the Club, wearing one of those jackets with suede at the elbows, discussing geological sediment layers, Pangaea, and the structures of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge."

Richard shows us just how different life can be for one who lives in the sky, even when on the ground. In scheduling a training rendezvous, Dan was likely to tell Richard "he'd be flying over the house around 9:30 and did I want to join him." They meet in the air like the rest of us meet at Starbucks. I want to hang out with these guys.

Toward the end of Richard's training, Dan asks: "I've been thinking about flying my 'Rey to Seattle. You'll be on your way pretty soon. Would you mind if I flew alongside?" And thus a flight of two was born.

Their westward journey begins, a pair of SeaRey amphibians: Puff and Dan's "Jennifer." The 'Reys are sisters almost. The odyssey has its share of adventure and danger: dodging submerged and sword-sharp mesquite trees on water takeoffs, dealing with stuck landing gear or leaky carburetors, avoiding thunderstorms and hail.

But with the challenges, they also share the quiet joy of solitude and the freedom of being in the air. Fifty-nine stops, 62 hours of flying time, their transcontinental flight takes them over and onto rivers and lakes and gulfs and deltas and airstrips and fields and sand deserts and canyons and mountains and beaches and thermal geysers and pine forests.

The theme of "freedom" rings a bell-like refrain through the pages of this book. "The SeaRey can go nearly anywhere, practically anywhen," Richard writes. "That's all the freedom I ask, to take her there as I wish."

Later and deeper into their journey, he reflects:

"It had been so long since what-day-is-it mattered that it was a funny bemusement, flying: could this be a Monday? No. Monday was a couple weeks ago. So it must be Friday. No. Is it Tuesday, then?"

Is there one among us who hasn't felt this freedom, if only once or twice a year on some extended vacation? Free of wristwatch or calendar or Blackberry and in a space where the concept of "day-of-the-week" just doesn't apply. That is glorious.

It was something of a disappointment to read a comment in Kirkus Reviews, which sniped: "Bach shows an odd insensitivity to people who have not made a fortune writing best-sellers. On one remote lake, he sniffs: `These places are a few miles from where some folks live, stressed in I-have-to lives. To get from there to here you need a quest, and a way to travel.'" The reviewer adds, "Not to mention lots of money."

I remembered reading Richard say that. I liked it. I felt understood. I'm not ashamed to admit I'm in an "I-have-to-life" at this moment. In Richard's writing, though, I felt the hope of freedom floating out there -- if I had the courage to reach out and take it. To work for it.

I certainly hadn't felt sniffed-at. I can only think that the reviewer felt snared in his own web of "have-to," and rather than being encouraged by Richard's words, felt taunted. Regardless, it's a shame the reviewer seems to have missed the sentiment so wildly.

Because in the end, this story is about flying, sure. And yes, it's about Richard's intimate friendship with that young lady, Puff. Of course. But what this story is really about is freedom. Freedom for any of us who would stand and take it.

Near the close of the book, Richard writes:

"We had nobody's permission but our own, and needed no other, to follow what we each most loved to do with our lives, which at that moment was to stand on this beach forsaken by every other human being. No footprints, no tire tracks, no nothin' but us four friends in the sunlight, clear cool water rippling like high-speed transparent rock while we stood nearby."

Richard speaks of what he and Dan had sacrificed to earn that freedom: "No golf, no bowling, no sports events, no drinking or card games with buddies on Saturday night. Gave it all up. To stand where we are standing. Now."

It seems a fair trade.

No comments:

Post a Comment